Mental health practices across the United States are under pressure. Demand is rising. Staffing is tight. Reimbursement rules keep changing.

In the middle of all this, many practices leave money on the table simply because they do not fully understand incident-to billing.

Incident-to billing is not new. Medicare has allowed it for decades. Yet, in mental healthcare, it is still widely misunderstood and often misused.

When done correctly, it can significantly improve reimbursement. When done wrong, it can trigger audits, recoupments, and compliance nightmares.

This guide explains incident-to billing in mental healthcare step by step.

Basics of Incident-to Billing

Before diving into the specifics of mental health, it helps to slow down and understand what incident-to billing actually is.

Incident-to billing allows certain services performed by non-physician practitioners or clinical staff to be billed under a physician’s NPI, at 100% of the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, instead of the reduced rate usually paid to non-physician providers.

That sounds attractive, and it is. But Medicare does not give this benefit freely. It comes with strict conditions.

At its core, incident-to means:

- The service is part of an ongoing course of treatment.

- A physician has already established the diagnosis and plan of care.

- The physician remains actively involved.

- The service is performed under direct supervision.

If any of those pieces are missing, incident-to billing does not apply.

Importance of Incident-to Billing in Mental Healthcare

Mental healthcare relies heavily on non-physician providers. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, licensed clinical social workers, psychologists, and counselors are the backbone of most behavioral health practices.

Here is the issue. When these providers bill Medicare directly under their own NPI, reimbursement is often reduced. For example:

- Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are paid at 85% of the Medicare rate.

- Some mental health professionals can not bill Medicare independently at all, depending on credentials and services.

Incident-to billing, when allowed, lets practices:

- Bill at the full 100% physician rate

- Improve revenue without increasing patient volume

- Better support collaborative care models

According to CMS, practices using incident-to correctly can see 10% to 15% higher reimbursement for eligible services. Over a year, that difference is substantial.

Who Can Use Incident-to Billing in Mental Health

This is where many practices get confused. Not every provider or service qualifies.

Physicians

Only physicians (MD or DO) can supervise and bill incident-to services. Psychiatrists are the most common supervising physicians in mental health practices.

Non-Physician Practitioners

In mental healthcare, incident-to services may be performed by:

- Nurse Practitioners (NPs)

- Physician Assistants (PAs)

- Clinical psychologists (in limited situations)

- Licensed clinical social workers or counselors, if they meet the “auxiliary personnel” criteria

The key is that Medicare considers these providers auxiliary personnel when they are acting under a physician’s plan of care and supervision.

Services That Qualify for Incident-to Billing

Incident-to billing does not apply to all mental health services. It works best for evaluation and management (E/M) and ongoing therapy-related care.

Common examples include:

- Follow-up medication management visits

- Established patient psychotherapy sessions

- Behavioral health counseling as part of a treatment plan

- Care coordination related to an existing diagnosis

Initial evaluations do not qualify. The physician must see the patient first and establish the treatment plan.

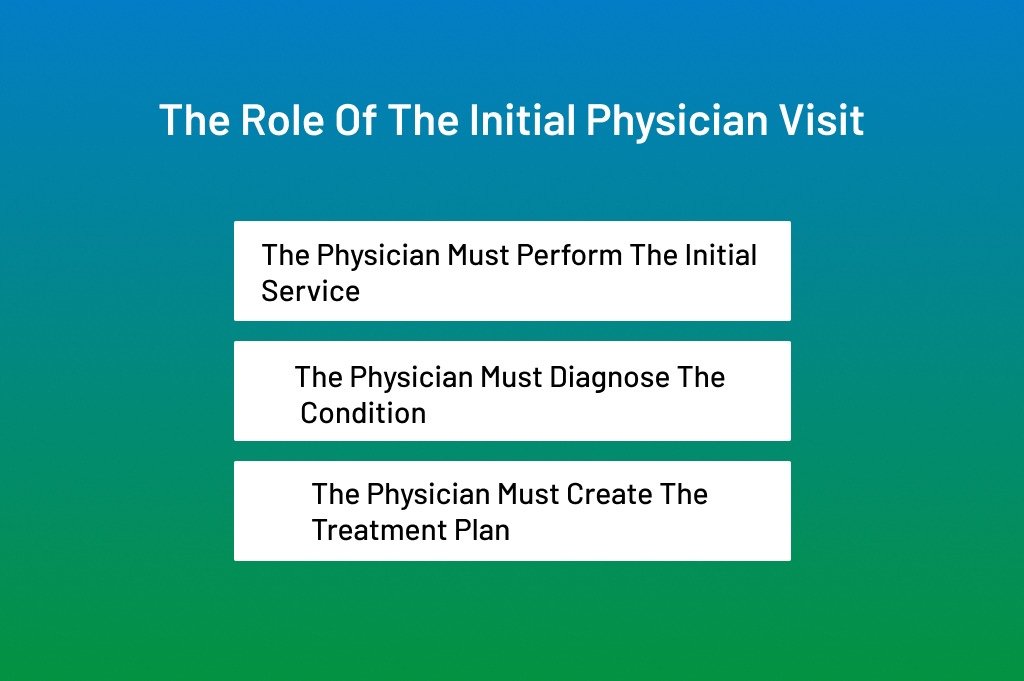

The Role of the Initial Physician Visit

This is the foundation of incident-to billing, and it cannot be skipped.

For incident-to to apply:

- The physician must perform the initial service

- The physician must diagnose the condition

- The physician must create the treatment plan

In mental health, this usually means:

- A psychiatrist conducts the initial psychiatric evaluation

- Diagnosis is clearly documented

- The medication and therapy plan are outlined

Only after this step can follow-up services be billed incident-to.

If a nurse practitioner sees the patient first, incident-to is off the table for that episode of care.

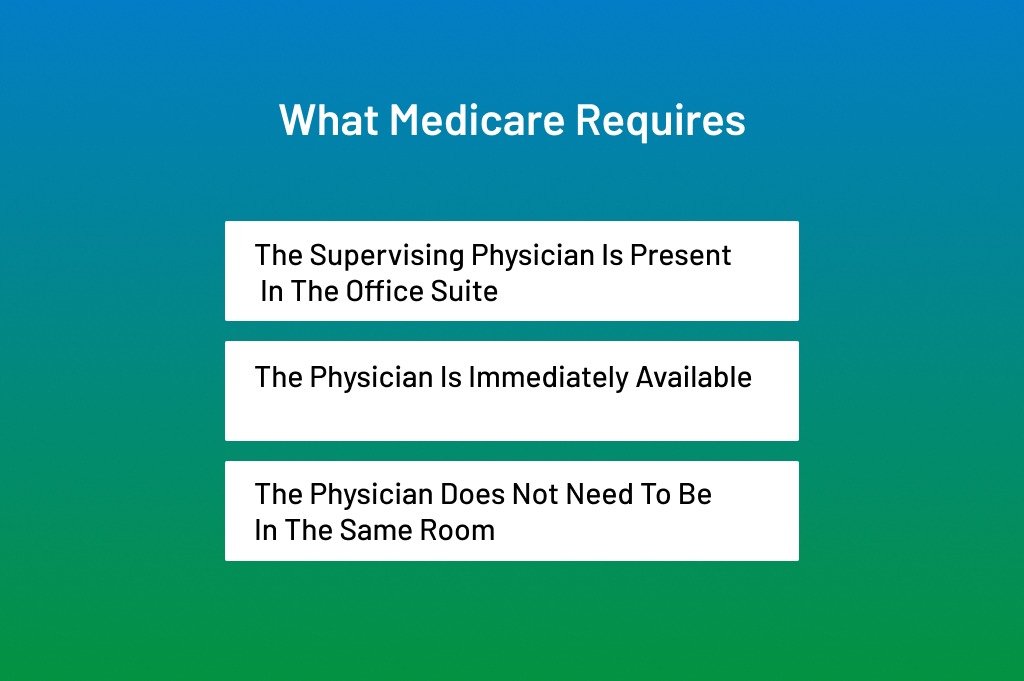

What Medicare Requires

Direct supervision is one of the most misunderstood rules in incident-to billing.

Medicare defines direct supervision as:

- The supervising physician is present in the office suite

- The physician is immediately available

- The physician does not need to be in the same room

For mental health practices, this means:

- Telehealth supervision usually does not qualify

- The psychiatrist must be physically onsite

- Coverage arrangements must be documented

During the COVID-19 public health emergency, CMS temporarily relaxed supervision rules. Many practices assumed those changes were permanent. They were not.

As of now, standard direct supervision rules apply again, unless CMS issues new guidance.

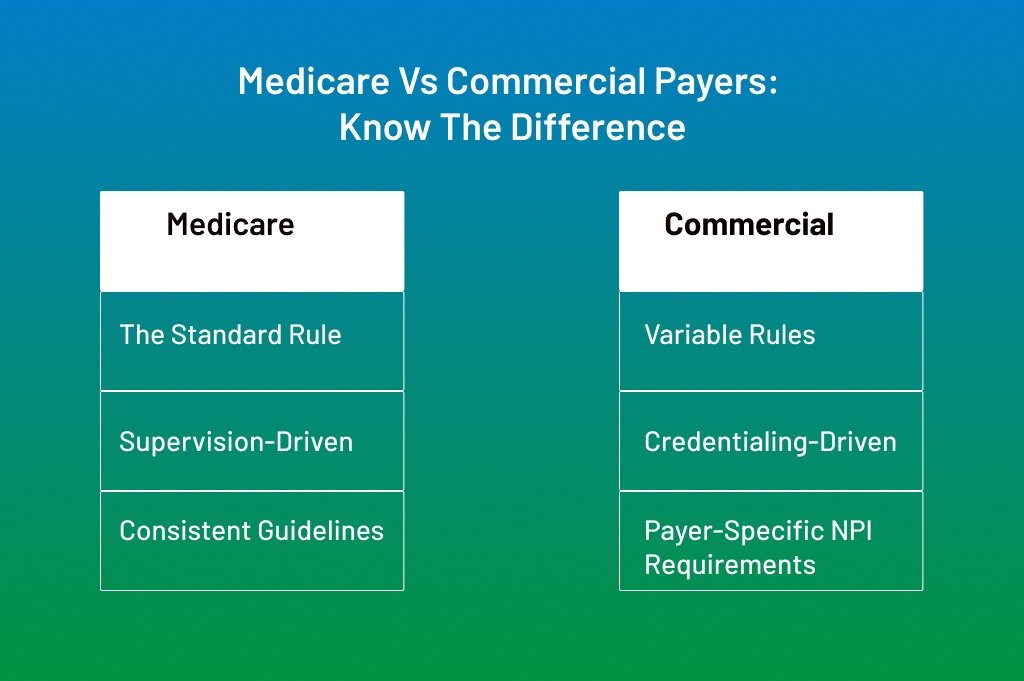

Medicare vs Commercial Payers: Know the Difference

Incident-to billing is a Medicare concept. Commercial payers may or may not follow the same rules.

Some commercial insurers:

- Allow incident-to-like billing

- Pay based on credentialing instead of supervision

- Require the rendering provider’s NPI regardless of supervision

This is why payer-specific rules matter. Never assume that incident-to applies across all insurers.

Innovative practices create payer matrices that clearly define:

- When incident-to is allowed

- Which providers qualify

- Documentation expectations

How to Use Incident-to Billing in Mental Healthcare

Mental healthcare billing looks simple on paper. In real life, it is anything but.

Practices juggle psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, therapists, care coordinators, and strict Medicare rules that leave little room for error. One billing concept that can either strengthen revenue or destroy compliance is incident-to billing.

Many practices hear about it from peers or consultants. Some try it once and get burned.

Others avoid it and lose legitimate reimbursement every month.

The truth sits in the middle. Incident-to billing works in mental healthcare, but only when you follow the rules step by step and document every move.

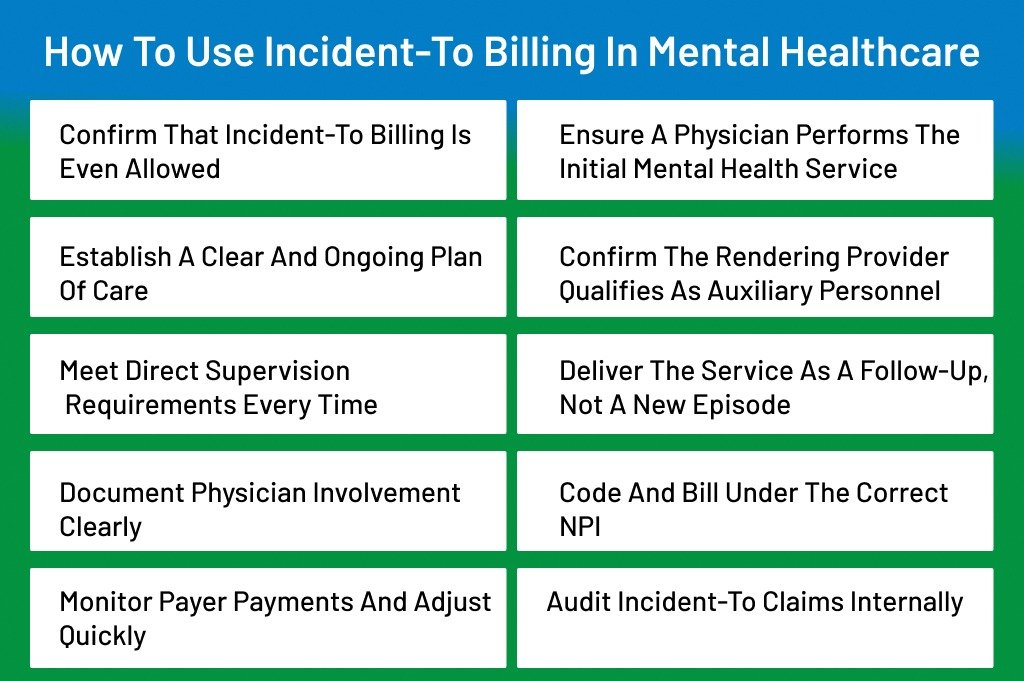

Here’s how to use incident-to-billing in mental healthcare:

Confirm That Incident-to Billing Is Even Allowed

Before you do anything else, you must confirm that incident-to billing applies to the payer and service. This step sounds obvious, yet it is often skipped.

Incident-to billing is primarily a Medicare concept. Original Medicare Part B allows it. Many commercial payers do not. Medicaid rules vary by state, and several states do not recognize incident-to billing.

From a billing standpoint, you should always start with payer verification. Check the patient’s insurance, identify whether Medicare is primary, and review payer manuals. A service that qualifies under Medicare may be denied instantly by a commercial plan.

Experienced practices maintain a payer policy matrix. This internal reference outlines which payers allow incident-to billing, under what conditions, and for which provider types. Without this step, everything that follows is guesswork.

Ensure a Physician Performs the Initial Mental Health Service

This is the backbone of incident-to billing. Medicare is obvious here.

For incident-to billing to apply, the initial service must be performed by a physician, typically a psychiatrist in mental healthcare. This initial visit establishes medical necessity, diagnosis, and the treatment plan.

In practical terms, this means the psychiatrist must:

- Evaluate the patient

- Diagnose the mental health condition

- Create a detailed plan of care

- Document that plan clearly in the medical record

If a nurse practitioner or physician assistant sees the patient first, incident-to billing cannot be used for that condition. No workaround exists. Auditors closely examine the first visit date.

This step alone accounts for a large percentage of incident-to denials seen in Medicare audits.

Establish a Clear and Ongoing Plan of Care

Incident-to billing depends on continuity. Medicare expects the non-physician provider to be carrying out a physician-directed plan, not practicing independently.

The plan of care must include:

- Diagnosis

- Treatment goals

- Medications or therapy approach

- Follow-up expectations

In mental healthcare, this often includes medication management combined with therapy or behavioral interventions. The plan should feel alive, not static. Medicare expects updates when symptoms change, medications are adjusted, or treatment goals evolve.

A common mistake is leaving the original plan untouched for months. That signals passive supervision, which weakens incident-to eligibility.

Confirm the Rendering Provider Qualifies as Auxiliary Personnel

Not every provider automatically qualifies for incident-to billing.

Medicare allows incident-to services to be performed by auxiliary personnel, which may include:

- Nurse practitioners

- Physician assistants

- Certain licensed mental health professionals working under supervision

The key is the employment or contractual relationship. The auxiliary provider must be employed by, leased to, or contracted with the physician’s practice.

Independent contractors outside the practice structure usually do not qualify. From an audit perspective, Medicare looks at payroll records, contracts, and organizational charts.

If the provider relationship is not clean, incident-to billing becomes a compliance risk.

Meet Direct Supervision Requirements Every Time

Direct supervision is one of the most misunderstood aspects of the incident-to rules in mental healthcare.

Medicare defines direct supervision as the physician being physically present in the office suite and immediately available. The physician does not need to be in the same room, but must be on-site.

For mental health practices, this means:

- The psychiatrist must be in the office on the date of service

- Remote supervision does not qualify

- Coverage arrangements must be documented

During public health emergencies, CMS allowed temporary flexibility. Many practices built workflows around that. Most of those flexibilities have ended.

From a compliance standpoint, if the supervising physician is not physically present, incident-to billing should not be used. Billing under the non-physician’s NPI is safer.

Deliver the Service as a Follow-Up, Not a New Episode

Incident-to billing only applies to established patients and ongoing care. The service must be a continuation of the physician’s treatment plan.

In mental healthcare, common qualifying services include:

- Follow-up medication management

- Established patient psychotherapy

- Behavioral health counseling is aligned with the plan of care

New complaints, new diagnoses, or major changes in treatment direction often require physician involvement. When the non-physician provider steps outside the established plan, the incident-to no longer applies.

This is where clinical judgment and billing judgment must align.

Document Physician Involvement Clearly

Documentation is where incident-to billing either survives or collapses.

The medical record must show:

- The physician’s initial evaluation

- A defined plan of care

- Evidence of physician involvement over time

- Notes from the auxiliary provider referencing the plan

Physician involvement does not mean signing every note. It means active management. That can include periodic check-ins, medication changes, or documented oversight.

Auditors look for patterns. If the physician disappears from the record after the first visit, incident-to claims become vulnerable.

Industry data shows that documentation deficiencies account for more than half of incident-to recoupments in behavioral health audits.

Code and Bill Under the Correct NPI

When all incident-to conditions are met, billing is straightforward.

The service is billed:

- Under the physician’s NPI

- Using the appropriate CPT code

- Without modifiers indicating non-physician care

For example, an established patient E/M visit performed by a nurse practitioner may be billed under the psychiatrist’s NPI if the incident-to rules are satisfied.

If even one requirement is missing, the claim should be billed under the non-physician’s NPI. Accepting the reduced reimbursement is better than risking an audit.

Monitor Payer Payments and Adjust Quickly

After submission, review the remittance advice carefully. Some payers reprocess incident-to claims differently than expected.

Look for:

- Correct reimbursement rates

- Unexpected downcoding

- Denials tied to rendering provider mismatch

Patterns matter. If a payer consistently rejects incident-to claims, revisit policy guidelines. Do not force a billing strategy that a payer does not support.

Audit Incident-to Claims Internally

Incident-to billing should never be “set it and forget it.”

Strong practices perform internal audits at least quarterly. They review:

- Physician presence logs

- Documentation consistency

- Provider schedules

- Claim accuracy

This proactive approach catches problems early. It also shows good-faith compliance if Medicare ever audits the practice.

Final Thoughts

Incident-to billing in mental healthcare is not a loophole.

It is a structured Medicare policy that rewards coordinated, physician-led care. When followed step by step, it can improve reimbursement while staying compliant.

The key is discipline. Clear workflows. Strong documentation. Conservative judgment when rules are unclear.

Practices that respect the incident-to rules use it as a strategic tool. Practices that push boundaries often come back to bite you later.

FAQS

Who can supervise incident-to services in a mental health practice?

Only a physician, usually a psychiatrist, can supervise incident-to services under Medicare rules. The supervising physician must be actively involved in the patient’s care and must be physically present in the office suite on the date of service. Supervision cannot be delegated to another non-physician provider. Clear scheduling and coverage documentation are essential to support compliance.

Can incident-to billing be used for new mental health patients?

Incident-to billing does not apply to new patients or new conditions. Medicare requires the physician to personally perform the initial evaluation and establish the diagnosis and treatment plan. Follow-up services may qualify only after this first visit is completed and documented. Skipping this step leads to automatic non-compliance.

How does incident-to billing affect reimbursement rates?

When billed correctly, incident-to services are reimbursed at 100 percent of the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. The same services billed under a non-physician NPI are typically paid at around 85 percent. Over time, this difference can have a noticeable impact on practice revenue. Accuracy matters because improper billing can trigger recoupments.

Does incident-to billing apply to telehealth mental health visits?

Most telehealth services do not meet Medicare’s direct supervision requirement for incident-to billing. The supervising physician must be physically present in the office suite, which telehealth encounters usually do not allow. Practices often need to bill these visits under the rendering provider’s NPI instead. Temporary flexibilities should never be assumed to be permanent.

What documentation is most important for incident-to claims?

The medical record must clearly show the physician’s initial evaluation, the established plan of care, and ongoing physician involvement. Notes from non-physician providers should reference and follow that plan. Repetitive or outdated plans weaken compliance. Auditors focus heavily on documentation consistency across visits.

Can incident-to billing be used with Medicaid or commercial insurers?

Incident-to billing is primarily a Medicare concept. Many Medicaid programs do not recognize it, and commercial payer rules vary widely. Each payer’s policy must be reviewed before applying incident-to workflows. Assuming Medicare rules apply to all insurers often leads to denials and payment delays.